Story by Michael Shay

“The vessel sprung a leak soon after we sailed from Benecia, California . . . and twelve men were detailed to man the pumps,” Pvt. Phillip Brack wrote. Brack’s adventure was retold in Orvil Dodge’s Pioneer History of Coos and Curry Counties, Oregon, published in 1898. The transport schooner, Captain Lincoln, pushed northward in a heavy gale, carrying Brack and 35 U.S. Army Dragoons (mounted infantry), led by Lt. Henry Stanton. They’d been sent to reinforce and resupply a newly established fort at Port Orford on Oregon’s southern coast.

According to William Henderson Packwood, another dragoon on board, giant waves smashed two of three whaleboats used as lifeboats on the Captain Lincoln. As the hold filled with water, there “was an ugly feeling among the men, and a fight would have resulted for possession of the [remaining] boat,” he said.

The leak grew worse as they neared their destination and the strengthening gale prevented them from entering Port Orford. “Our captain seemed to conclude that the only salvation for us was to hunt a beach where he could sail near enough to save . . . his many passengers,” Brack said.

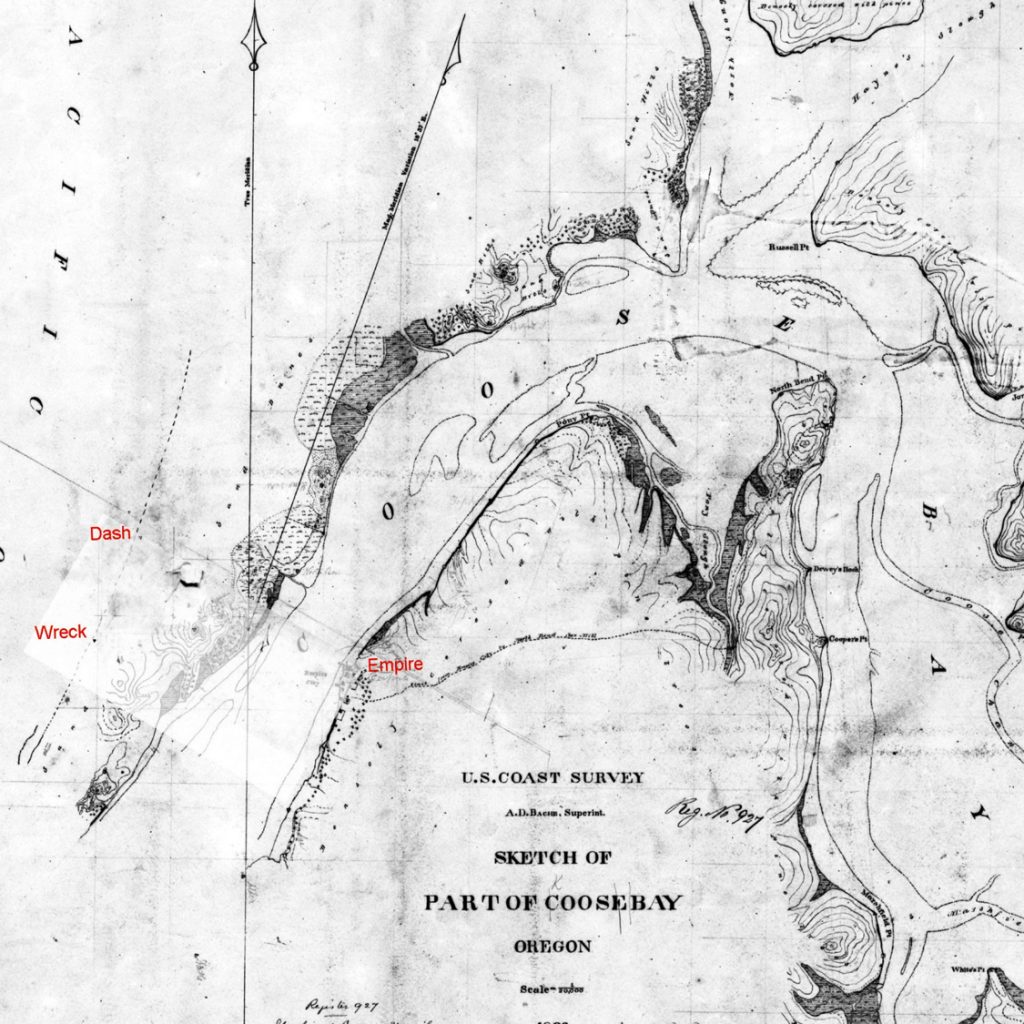

Swept north, the schooner struck a sand bar just past Coos Bay in the early hours of January 3, 1852. “She settled down to the bottom and for awhile the breakers rolled over her decks,” Brack reported.

Henry Baldwin, another Dodge informant, was below the deck with most of the men at the time. “Neptune’s flood descended, deluging the hapless sons of Mars who were below in dreams,” he wrote. But as the incoming tide lifted the ship over the bar, “the wounded skimmer of the seas bounded onwards . . . until she struck wild Cowan’s sands,” Baldwin said.

As the tide receded, stranding the vessel in five feet of water, the dragoons shared two buckets of well-spiced, hot grog. “Never did . . . the contents from the flowing bowl taste so good,” Baldwin wrote.

When the sun finally rose, the sailors and dragoons disembarked. They soon discovered a freshwater lake in a nearby stand of trees and hoisted the schooner’s galley ashore, placing it on a nearby ridge overlooking the future Camp Castaway. Then they began the five-day task of salvaging parts of the ship and her cargo.

“First came cases of ammunition, then some commissary stores, with eight or ten barrels of whisky,” Baldwin said. Apparently the men put the whiskey to good use, as it didn’t appear on the final list of salvaged stores!

The next day, native Hanis people from a village at present-day Empire arrived on the scene. By words and signs, Stanton assured them his men meant no harm. A larger party from the Hanis and other Coos villages arrived the next day with a “long pack train of squaws laden with fish of all kinds, wild geese, ducks, elk, and venison,” Baldwin reported.

The natives made many such visits during the dragoons’ four-month stay. “In return for abundant presents,” Baldwin said, the soldiers traded “hardtack, rice, tobacco and lots of dragoon pants, shell jackets, capes, skirts, boots, and shoes, which pleased them extremely well.” With help from the Coos people, the dragoons finally completed the unloading. Using spars and sails, they made tents to shelter themselves and to protect their supplies. “In a few days quite a large, neat and handsome sail-cloth village had raised its head and graced the sands of that then wild beach,” Baldwin said.

Even as the construction of Camp Castaway proceeded, Lt. Stanton turned his attention to exploration and the problem of his salvaged cargo. Six days after the wreck, he set out with a small party of dragoons for Port Orford. He paddled across Coos Bay in his remaining whaleboat, and then made his way south to the mouth of South Slough near present-day Charleston. After struggling over Cape Arago and traversing over the daunting Seven Devils, he gave up and returned to camp. In a few days, he followed the beach north to the new town of Umpqua City seeking buyers for his stores, but found no takers.

On January 16, several men from Umpqua City visited Camp Castaway, telling Stanton they would soon be sailing for San Francisco. Stanton had them take a letter to the U.S. Army headquarters in Benicia, detailing his situation.

After news of the Captain Lincoln and Camp Castaway reached Benicia, Captain Morris Miller received orders to take charge of the stores. On April 4, Miller left for Port Orford on a steamer bound for the Columbia River.

During a violent night storm on April 6, the steamer’s captain tried to drop Miller off at what he thought was Port Orford. “The surf could be seen distinctly breaking with great force on the beach,” Miller wrote in The Annual Report of Secretary of War, December 4, 1852. “Several fires were burning near the water’s edge,” he added.

The captain fired two guns, but when no signal came back, he set a course for the Columbia River. Later, Miller discovered they had almost put in at the Rogue River, where the natives were hostile. “Had I succeeded in landing, the result would have been unfortunate—perhaps fatal,” he reflected.

Captain Miller finally arrived at Port Orford on April 12, finding about 20 men from Company L and 12 of Lt. Stanton’s dragoons quartered in log houses. The dragoons had come to the fort with another letter to Benicia, and were waiting for a reply.

Miller left for Camp Castaway with 20 mules and 10 dragoons on April 20. They crossed multiple rivers with help from the Indians, and then traversed the Seven Devils, “a constant succession of ridges and precipitous gullies and creeks at the bottom,” Miller wrote. After swimming his mules across the Coos River on April 25, he arrived at Camp Castaway.

“The camp was near the point where the wreck had occurred, on the sand-spit lying between Kowes River and the Pacific—a very dreary position,” Miller wrote. He complained that clouds of blowing sand penetrated every canvas covering and “besprinkled” all of the soldiers’ food.

Prior to leaving Camp Castaway, Miller had sent two wagons to Umpqua City on the brig, Fawn. On April 26, he took his mules up the beach to retrieve them. Like Stanton, he found no bidders for his salvaged stores, so he chartered the schooner, Nassau, to pick up the supplies at Coos Bay and take them to Port Orford.

The transport of goods from Camp Castaway to the Coos River for loading began April 30, when the wagons arrived. By May 4, when the Nassau hove in sight at Coos Bay, the stores were ready to load. Having previously sounded the harbor in the whaleboat, Captain Naghel, commander of the Captain Lincoln, piloted the Nassau over the bar. “She triumphantly entered the river at low water, finding three-and-a-half-fathoms on the bar by lead line,” Miller wrote.

Lt. Stanton, and his men completed the loading by May 9—Miller having left for Port Orford with four dragoons two days prior. The Nassau arrived at Port Orford on May 12 with the salvaged cargo, remaining dragoons, and sailors. She finally sailed for Benicia and arrived on May 24 with Captain Miller and the crew from the Captain Lincoln.

In his final report, Miller said the native people on the coast demonstrated “the most friendly disposition, aiding us readily with their canoes in crossing the rivers, bringing wood and water to the campfire, and considering themselves amply remunerated . . . by a small quantity of hard bread. They are full of curiosity . . . and much disposed to barter,” he said. “In my opinion, no difficulty need be apprehended from them, unless it originate in aggressions of the whites.”

Unfortunately, Miller proved correct. Knowledge of the country gained during these events and the discovery of a harbor at Coos Bay soon grabbed the attention of pioneers. When they discovered gold on the beaches, the rush began.

As gold mining operations developed on South Coast beaches, 20 men from Jacksonville, Oregon, formed the Coos Bay Commercial Company. They moved their families to Coos Bay in the fall of 1853, establishing Empire City and Marshfield.

As more pioneers arrived on the South Coast, they fenced the land and allowed their livestock to destroy natural resources important to the native people. Conflict between pioneers and Indians erupted in the Rogue Indian wars of 1855−56. Even though the Coos did not participate, they were rounded up and sent to live with Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians near a new fort on the North spit of the Umpqua River in 1856. This marked the end of a lifeway that had been enjoyed by the Coos people for perhaps thousands of years. ■

CAMP CASTAWAY REDISCOVERED

Using field notes and maps from a West Coast survey conducted for the U.S. Navy in 1861, archaeologist Scott Byram rediscovered the exact location of Camp Castaway in 2010. Byram explored the site over the next two years, using ground-penetrating radar and limited sub-surface surveys. He recovered ferrous metal fragments, ceramics, copper nails, percussion caps, and other artifacts.

In consultation with the Bureau of Land Management (BLM); the Confederated  Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw Indians; the Coquille Tribe; and the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, Byram coordinated with the Southern Oregon University Laboratory of Anthropology (SOULA) to investigate further. Directed by Mark Tveskov in July 2012, students in the Southern Oregon University archaeological field school conducted test excavations at the site. Volunteers from the BLM; the Confederated Tribes of the Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw; and the Coquille Indian Tribe participated.

Tribes of Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw Indians; the Coquille Tribe; and the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, Byram coordinated with the Southern Oregon University Laboratory of Anthropology (SOULA) to investigate further. Directed by Mark Tveskov in July 2012, students in the Southern Oregon University archaeological field school conducted test excavations at the site. Volunteers from the BLM; the Confederated Tribes of the Coos, Lower Umpqua, and Siuslaw; and the Coquille Indian Tribe participated.

Though drifting sand, vandalism, and railroad construction had heavily impacted the site, the team uncovered more than 1,200 artifacts. The artifacts confirmed written reports of the wreck and occupation of North Spit by the dragoons. They included vessel-related hardware; percussion caps and lead balls; domestic materials related to food preparation, heating and lighting; and personal items such as whiskey bottles, a medicine container, and a military button.

SOULA confirmed this was the site of Camp Castaway and that it’s possible “thick clusters of artifacts or living floors remain buried.” In their final 2015 report, SOULA recommended the site be added to the National Register of Historic Places, saying research there could inform discussions about the establishment of the Oregon Territory and interactions between Native Americans and the earliest Euro-Americans. In addition, SOULA pointed out the site is associated with several prominent Oregon pioneers who first came to the territory as U.S. Army dragoons, including Henry H. Baldwin, Phillip Brack, George H. Abbot, and William Henderson Packwood.

THE “BALDWIN TREE”

There is one other legacy of the wreck at Camp Castaway that still survives—a cypress tree. The tree, located in Bandon, is called the “Baldwin Tree.” Local lore says it was planted by Henry Hewitt Baldwin, a dragoon on the Captain Lincoln, one of several men who made a hike back to Port Orford to communicate about the wreck of the Captain Lincoln on Coos Bay’s North Spit. Baldwin was a native of Bandon, Ireland, and was a boyhood friend of “Lord” George Bennett, the eventual founder of Bandon. Baldwin moved to the Bandon area before Bennett, and helped him get the town established. After homesteading on nearby Bear Creek, Baldwin built a home on the ocean cliffs in Bandon, retired there, and died in 1911. Although Baldwin’s home was destroyed in the great Bandon Fire of 1936, the tree was spared. —Steve Greif

This story appeared in the September/October 2017 issue of Oregon Coast magazine.

FURTHER READING

■ Bancroft, Hubert Howe. The Works of Hubert Howe Bancroft, Volume 30, Oregon II, 1848−1888. San Francisco: The History Company, publishers, 1888.

■ Clark, Robert Carlton. Military History of Oregon, 1849-59. Oregon Historical Quarterly, volume 36.

■ Dodge, Orvil. Pioneer History of Coos and Curry Counties, Oregon: Heroic Deeds and Thrilling Adventures of the Early Settlers (1898). Salem, Oregon: Capital Printing Company, 1898.

■ Douthit, Nathan. A Guide to Oregon South Coast History: Traveling the Jedediah Smith Trail. Corvallis, Oregon: Oregon State University Press, 2007.

■ McArthur, Lewis. Oregon Geographic Names. Oregon Historical Quarterly, volume 45.

■ Miller, Morris S.: The Annual Report of Secretary of War, December 4, 1852. Google Books.

■ Packwood, William. “Ship Wreck on Coos Bay in 1851.” Coos Bay Times, Coos Bay, Oregon.

■ Tveskov, Mark; Johnson, Katie; Rose, Chelsea. Archaeological Investigations of Camp Castaway and the Wreck of the Transport Schooner Captain Lincoln. SOULA Research Report 2012.07. Ashland, Oregon, 2015.

■ Victor, Frances Fuller. The Early Indian Wars of Oregon. Google Books.